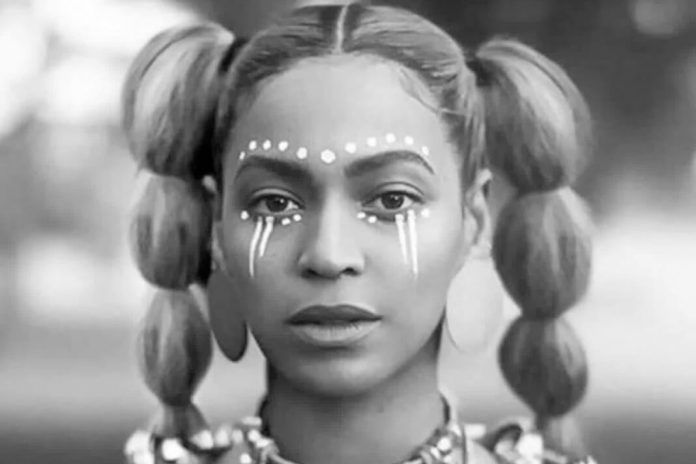

I haven’t watched or heard Lemonade. I haven’t read bell hooks’ critique. I haven’t read any think pieces related to Beyonce’s latest work nor do I intend to. But from what I gather from my social media feeds, bell hooks offered a lengthly, inaccessible, and inconsistent critique of the pop star. From what I hear, the noted scholar opined that Beyonce’s feminism is based on a harmful capitalistic value system that determines her feminism unworthy and unreal.

I’m not here to defend or dispute Beyoncé or bell. I’m here to reflect.

When I first embraced Black feminism as a spiritual and political foundation, I was arrogant in my application of Black sexuality. I gave myself freedom to identify as sex-positive but was selfish in recognizing sex-positivity in other Black women. I was (and still am) extremely antagonistic and suspicious of the theirstorical relationship between capitalism and Black feminine sexual freedoms, and was steadfast in harshly critiquing the ways that rich Black women — with their class privilege and cultural influence — used their sexuality as an exclusive means to sell music, brand themselves, and ultimately make white men more wealthy.

I was (and still am) further cognizant of how colorism determines who gets to be a publicly rich, Black, and sexually unbound femme.

I do believe that rigorous dialogue and action is needed to comprehensively unpack the intersectional dynamics of rich able-bodied Black women using sexuality as a means to reinforce white supremacist patriarchy. I do believe that analyzing the ambiguities of bodily autonomy, sexual expression, and cultural production under the engine of capitalism is commendable and groundbreaking scholarship.

But deciding which Black people get to self-identify as Black feminists is a form of violence.

I’ve committed this violence when I was respectable and unclear. I’ve written articles that challenged the genuineness of Beyoncé and Nicki Minaj‘s sexualities; they were not autonomous beings with creative control and artistic license … they were strategic capitalists without morality or Black pride. I mocked their supporters as unintelligent; they were unable to see the sinewy strings of capitalism tugging at their Black femme bodies.

I was arrogant and wrong.

I was also envious. As a Black women with deep insecurities, I wanted desperately to evoke similar levels of confidence and authority with the likes of Beyonce, Nicki, and Rihanna. I wanted to singlehandedly transform the flow and core of the Culture; to impact the social dynamics of global Blackness with the unrestrained force of my vagina.

In the midst of my internal struggles, I erroneously and violently dictated who could come into Black feminism and womanism.

But how I exist now, I am profoundly committed to ensuring that Black feminism and its multilayered iterations are accessible to all Black women.

And through this commitment, I wholly accept how Black women and femmes navigate in their ideological systems. Although I have stake due to my Black-woman-queerness, I do not have unilateral ownership of Black feminisms. No one does — not even the most trained or richest of us.