We’ve done nothing, but we’re hated widely.

In high school, I was part Cherokee. Until someone clapped back with the proverbial “Bish WAYUR?!” I was also “Jamaican and Black” because, according to family legend, I had a verrrrryyyyy distant relative who came from the island in the 1800s.

But my Black American existence — from the food I ate, to music I listened to, alongside my colloquialisms sprinkled in the thick of my New York City accent — was always with me, even when I failed to recognize it.

Growing up Black American meant feeling culturally displaced. I didn’t know how to be a Black American because our cultural, religious, and social traditions were violently erased from history, forgotten in the throes of today, and flagrantly whitewashed to the point where these esteemed customs (whatever they are) are frustratingly unrecognizable.

Being funneled through the public school system meant that the only access I had to my ancestral history was the one chapter in the history textbooks which represented slavery and the Civil Rights Movement as a momentary lapse in America’s moral character that would ultimately see redemption.

Being Black American meant not having family and friends beyond the nation’s borders that I could visit during summer. It meant not speaking another language or dialect. It meant seeing West Indian women as mean-spirited and sexually available, and Africans as a tried-and-true punchline to every joke.

To be a Black American means to exist in a void.

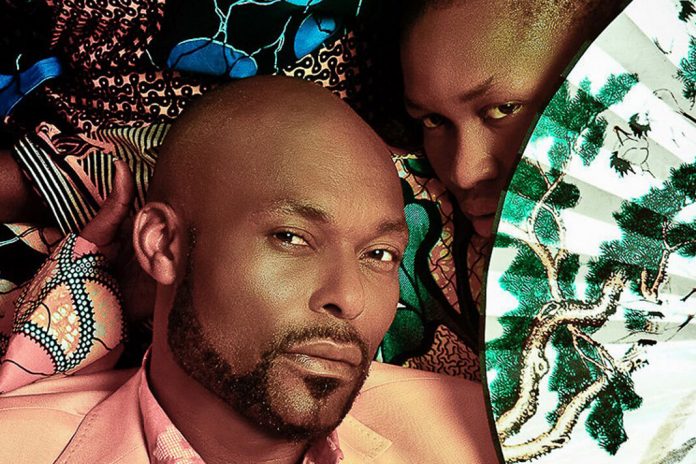

A weak ass recently published article about Black Americans culturally appropriating African prints made the rounds last week, and of course, the backlash was swift. The author of the controversial post based her analysis on Afropunk, the annual festival of Black love and counterculture where Black folk donned in African prints and other fashion staples, were prevalent.

Tia Oso’s response to the tone-deaf nonthink-piece was brilliant in its thoroughness. She highlights the glaring (and rather obvious) reality that folks at Afropunk represent the extreme diversity of the African diaspora of which Black Americans are a part, all while giving a tightly packed crash course into how cultural appropriation is defined by the institutional power of the appropriator, and the scaled oppression of the appropriated.

But articles aside, I sense a very palpable tension between Black Americans …and everyone else.

I feel this tension when I get my hair braided. One time, an African woman tugged my dry super-thick hair with the smallest comb she could find. She soon gave up, screamed at me in broken English, and passed me off to a more patient colleague better skilled in natural hair care. Six hours of being derided and scoffed at in a language I couldn’t understand was a less-than-pleasant experience. And I certainly couldn’t help but think that if my skin were white, I would’ve been treated more kindly.

I feel this tension when first generation Black folk espouse the same colorblind and respectability language that my white oppressors do.

I feel this tension when my Black friends from other countries confess to me they are disgusted by how much Black Americans take for granted — like free education and health care, no matter systematic flaws — when their countries of origin are often marred by war, fundamentalist terrorism, extreme poverty, and state-sanctioned gender-based violence.

But I’m clear; underlining all these intersectional tensions is white supremacy.

We must understand how (and in what ways) white supremacy has defined, reshaped, and mischaracterized Black Americans.

White supremacy has marvelously detached us from our history. Not knowing where we are from has fundamentally stunted us in far too many ways to name. I strongly believe that when communities can readily grasp their historical selves, they are more inclined to self-determine their futures.

To exist in America means to strip away unique cultural identity for mass assimilation. Black Americans were forced to. The process, set in motion for centuries, is in no way complete — cultural vessels will always remain, adapt, and/or reformat — but it was thorough enough that these essential cultural remnants are now extremely sporadic and are far from commonplace.

Behind enemy lines.

There’s also the basic fact that we live with our oppressors. Violent suppression of cultural, religious, social, and economic self-determination is not unique to Black Americans. But as Black Americans, we live deep behind enemy lines, which means our oppression is especially suffocating because we’re constantly reminded of it. Whiteness encroaches upon us daily and invisibilizes our existence.

Furthermore, the enemy is extremely crafty, and has layered our oppression via unjust laws, unresponsive bureaucracies, and other structural mechanisms … all while promoting just a few of us as puppets and tokens.

Our oppressors have isolated us from our own People.

I saw a glimpse of such isolation during the Idris Elba scandal, when some Black folk in England criticized Black Americans for not understanding the nuances of the actor being called ” too street.” Critiques went further to say that Black Americans are, on the whole, uninformed about what it means to be Black outside the States.

Black Americans are geopolitically maligned within the global space. And the revisionist and depleted education system in America ultimately prevents us from having formidable knowledge appropriate for an extensive Black worldview.

But we’re trying.

Divide and conquer.

Our oppressors have divided us to the point where we are fighting ourselves. Our oppressors have socially engineered us so we have an easier time seeing the differences amongst us, yet have trouble seeing our collective unity and overlapping cultural identities.

But I know we can unlearn this divisive behavior and continue recognizing and fighting the sameness of our enemy.

I share Tia Oso’s hope: “In love, I invite my brothers and sisters on the continent and throughout the diaspora to explore ways to connect and build relationships. These conversations are important and I hope they can be a source of healing and empowerment towards further collective liberation.”